Here is the next interview, the first in a bunch on the subject of Caricature.

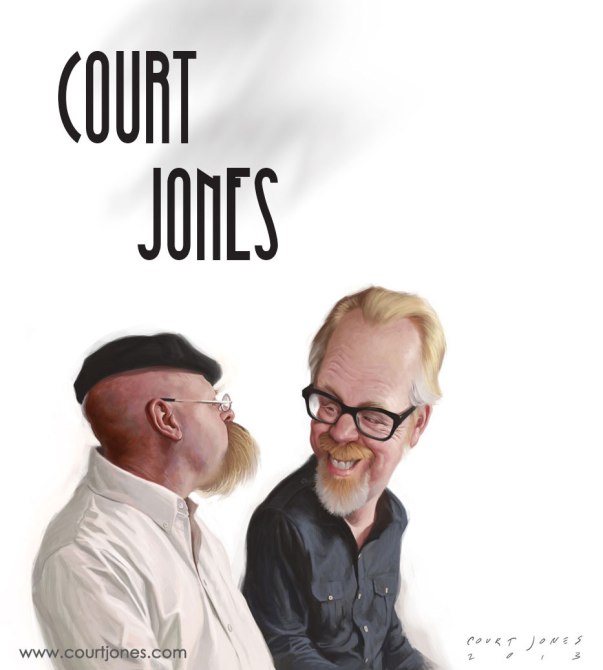

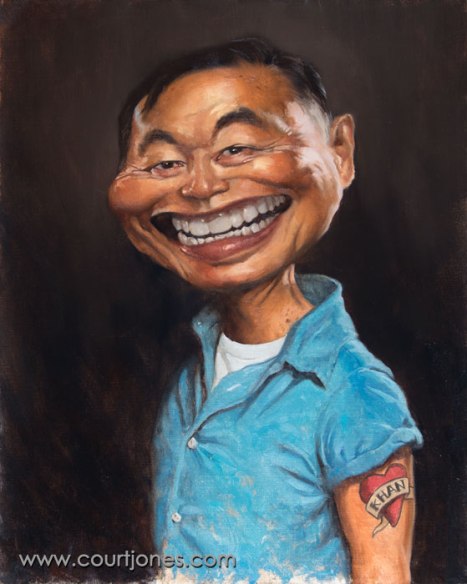

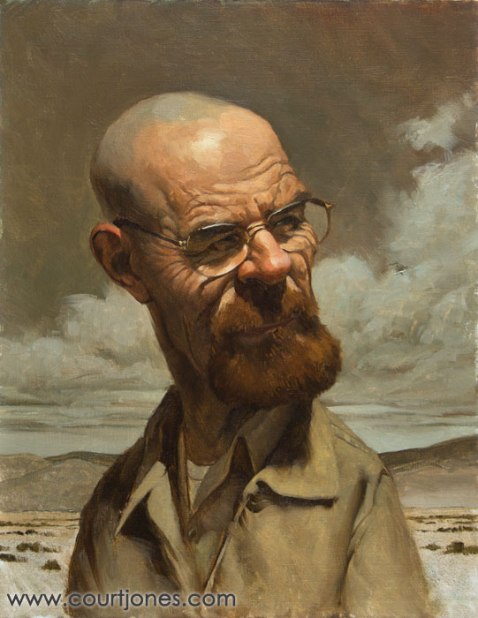

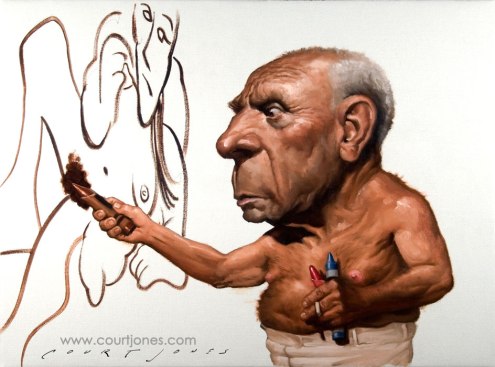

I was put onto Court Jones a while ago by listening in on Will Terrel’s Youtube channel. Court is amazing artist in general, and through caricature he captures not just laugh out loud likeness and great exaggeration, but the emotion of his subjects giving them a truly candid and authentic feel. He has a really amazing outlook on the world of art, and gives incredible insight into his processes, his struggles and ways to persevere in art and life. So I hope you enjoy this interview and please visit his amazing websites:

www.courtjones.com for his Caricatures

and

www.crjonesart.com for his portrait work.

Without further ado here is Court.

My first question to you is pretty straight forward: What got you into caricaturing? And what keeps you engaged with it?

I first dabbled in caricature in high school. Although I didn’t seriously consider it as a focus for my art career then. I had no idea then what I wanted to do in art exactly. But after college, I found a job drawing at a local amusement park, which is where I learned the basic skills of caricature. After a few years, I quit that to focus on freelance event entertainment and illustration. Live quicksketch art is usually looked down upon and misunderstood because there are many unskilled artists out on the streets giving the art form a bad name. But it can be a really challenging and sophisticated form of art, if you treat it that way. And drawing live in front of people for hours on end is great practice and a tremendous motivator to hone your skills at not only capturing a likeness, but to improve your calligraphy and just learning to be bold and unforgiving in your decisions. Doing it live, you learn that you can get away with quite a lot when you push the exaggerations. But what I get the most satisfaction from is doing oil painted caricature portraits and illustrations. Sebastian Kruger’s books are what opened my eyes in the late 90s to what extreme caricature as high art can look like–and how it can totally contradict what most people think of as caricature art. I had no idea you could do that until I saw his books. But what I try to do in my own studio caricature work is not be so much an extreme exaggerator, but I try to bring together elements of traditional portraiture and expressive painting techniques to exaggerated likenesses. I love when a funny caricature portrait is handled very seriously with a subdued palette and a fine art level of finish. I think the contrast is very engaging to a viewer.

When you come to caricaturing someone, what do you look for first and how do you know if it has been successful?

For me, it all starts with the shape of the head. How I push or stretch the shape of the head sort of determines where everything else will go and how I will change the relationships between the features for a humorous effect. I usually do scratchy thumbnail sketches that take only a minute or two. If I can see a likeness in that early stage, without any fancy rendering, then I know it will ultimately work.

When you struggle with a piece, what is your method for moving through the frustration?

When I am having a hard time with a likeness (and that happens a lot), I fall back on my fundamentals. Just like in sports, if you have better training in fundamental skills, you will be able to work through the tough spots. In my case, if rough thumbnail sketches aren’t working, I will use various exercises and techniques I have learned over the years. I might try different mediums and tools to draw with. Doing that sometimes helps get you out of a rut or helps keep you from making the same mistakes when sketching a face. I might try an approach to structured portrait drawing I learned at the Watts Atelier, which is a type of linear abstract lay-in originally taught by illustrator Frank Reilly. It’s usually used to build up a solid, three-dimensional looking portrait or figure drawing. But I have found it works beautifully for caricature, especially when doing extreme exaggerations or extreme angles or head tilts. There are a few other tricks you can do to overcome road-blocks, like doing a very tame portrait-y caricature sketch where the likeness is very strong, but isn’t very exaggerated or funny. But then I will do a caricature of that drawing. And then do a third drawing which caricatures the second drawing. It’s sort of like baby-stepping your way to a funnier likeness.

Is there someone else’s work that you can always return to for inspiration?

There are so many people whose work I check out for caricature inspiration. Just a few of them are Jan Op De Beeck, Sebastian Kruger (But only his older stuff. He does more tame pop-portraiture now), Jason Seiler, David O’Keefe, John Kascht. They make great exaggeration decisions and have really sophisticated and distinctive techniques. But there is a large range of traditional fine artists and illustrators I admire and would like to have reflected in my work, such as Jeremy Lipking, Mian Situ, Alex Ross, Jon Foster, and turn of the century artists like Sargent, Zorn and DeLaszlo. I know that’s a lot of different styles mixed in there, but I feel like there’s always at least one small speck of wisdom or inspiration you can learn from anyone.

What are your thoughts on the political/satirical niche that caricaturing takes in society? Do you see it as restricting the artform?

I don’t think that caricature needs to make any kind of political or social commentary. And good political or social satire doesn’t require caricature. They definitely CAN fit together nicely and are often used hand-in-hand. But that’s never been my purpose with caricature. For me, it’s just about exploring the ways in which a face and body can be re-arranged and exaggerated.

It’s a fun geometry problem for someone who was terrible at actual math.

The only thing that really restricts the art form are timid clients and art directors. In my experience, and my colleagues’ experience, we overwhelmingly have to subdue our exaggeration tendencies because they fear that our artwork will offend either the subject or the audience. Usually it’s when approval on a piece is decided by committee, rather than an individual client. That’s the absolute worst way to commission a caricature. So most artists learn to water down their true abilities in order to keep working.

What are your thoughts on the production art industry, specifically the processes of having an army of artists working on a single project like film and T.V?

I’ve used my caricature a bit in video game, TV and film production doing character design and illustration for branding and movie posters, and there is a lot of pressure to work within a very tiny range of expression. Developing a character or caricaturing a real person for film and TV makes clients get very nitpicky. And I can understand that. If they are going to invest lots of money animating these designs in 3D or printing them on marketing materials, they want to have things just right and have mass appeal. But entry-level artists should be aware of the high demands of that industry and not let themselves get upset by endless minor revisions. In those fields, I’ve only ever been hired as an individual freelancer, so I can’t speak about working among an army of artists. However, I did work on a very short term job doing storyboards in a cubicle for a video game company. And they demanded very high volume, if not precise drawings. So that was not really for me.

Beyond the basic principles of drawing and painting, when it comes to producing a piece, do you have a tried and true process, or is it a constant battle of problem solving?

I’m one of those artists that ends up trying a slightly different approach to each of my jobs. I change my materials and methods a lot because I enjoy the process so much. For example, I might start an oil painted illustration by using a warm toned surface on one day, or work digitally on a white background on the next job. Sometimes I keep the outlines of the drawing visible, and sometimes I don’t. Sometimes I’m precise and tight, and sometimes I paint more loosely. I’m not sure if this constant shifting is the best way to work. A lot of my portfolio is very inconsistent, which might be hurting me. But I tend to get a wide variety of stylistic requests from week to week, like a vintage pen and ink look, or a fully painted Rockwell style illustration, and everything in between. But I feel lucky to be able to do that kind of variety. I really enjoy the learning and experimenting. So I guess I’m more of a problem solver. Maybe one day I’ll hit upon that tried and true process.

How different is caricaturing to doing a normal portrait? Do you find one harder than the other?

I have found that this is a touchy subject with my caricature colleagues, because that discussion has come up before. Many of them think caricaturing is way more difficult than portraiture. I do both professionally, and I can say that portraiture is a lot more demanding and requires more training and practice to do really well. For me it does, anyway. Drawing and painting traditional portraits takes discipline and a very subtle eye for tiny errors. Whereas you can get away with murder in caricature and it can still look like the subject. And even with what I said earlier, clients are generally more forgiving when doing a caricature for them than they are when they commission a portrait. But, with that said, caricaturing IS a very difficult and specialized form of drawing and takes a lot of years of practice to do really well. And there is a wider range of acceptability by the public on what constitutes caricature, so it is easier to get work doing commissions and live entertainment. You don’t have to be really good to just make a living at it. But with portraits, you have to draw and paint at a pretty high level to continue getting work.

What are your thoughts on the growing competition in the art world, especially in high end illustration?

I can’t really speak to that. Sitting in my studio alone, it’s hard to gauge the level of competition out there. And I haven’t done a whole lot of what I would consider high-end illustration or apply to get in illustration annuals. But seeing that type of work produced in large volumes by my heroes is a bit intimidating. Following artists like Drew Struzan, Alex Ross, James Jean, Gregory Manchess and many others sort of makes me want to give up on illustration altogether sometimes. But I know I won’t give up because of that. It really just hits it home how much I still have to learn. And on top of that, I feel more of a pull right toward portraiture and traditional fine art these days. I think I’m putting more energy into portraiture and developing my painting dexterity lately because it’s what really motivates and excites me.

What importance do you place on caricaturing in the world of art? Why do think it’s still the number one style when it comes to satire?

Caricature is one of those things that has many applications across different fields of art: Character design for animation, political cartoons, editorial illustration, fine art and even portraiture all generally can have elements of caricature in them. To me, the essence of caricature is simply making conscious choices about what to change in your drawing to achieve a particular goal. In editorial illustration, it’s usually for humorous purposes. But in portrait painting, you can subtly caricature your subject to flatter them with a thinner neck and less wrinkles. The obvious advantage for caricature for humor and satire is that it automatically sets a tone of the ridiculous, before the story of the illustration is even established. Plus, since caricature is a forgiving art form, it works really well for simple cartoony renderings where you don’t have to spend hours and hours rendering it perfectly to get the message across. Great caricatures can be extremely simple and minimalist. Usually, a few simple, well-placed lines is often all that is needed to show a likeness of a major public figure.

At what point did you decide that you wanted to become a professional artist? When was the point that you realised that you made it?

I think I knew by the age of 10 or 12 that art was going to be my path. But I didn’t know exactly what kind of art I wanted to do at that time. And I don’t feel I’ve “made it,” in that I don’t feel like I’ve lived up to my potential or have been as consistently busy as other artists seem to be–or as well-known. But I have supported myself with art for the past 17 years doing honest work. And after several little successes and high points interrupted by longer periods of un-eventfulness and low profile jobs, I have started to realize that maybe making it is just a slow process of realization that builds up after many years until you’re able to earn enough money to start actually saving it. And it’s still work that makes me happy. So I’m not complaining.

What advice would you give to someone aspiring to be a professional artist, especially in the field of illustration?

Invest in a good education at an atelier, small school or private instruction working on your fundamental skills. Drawing is everything. It sometimes feels like a chore to me. I’d rather spend more time painting. But you’ll never be a good artist without focusing on your drawing. Painting at a high level is only really possible if you’ve put in hundreds or thousands of hours learning how to strengthen your core skills. And also, don’t waste any more time working at other jobs, putting off getting into an art career. If it really is your passion, put everything into it and find out what makes you excited about art. Look around to see what other people you admire are doing and find out how they do it.

Finally, do you have any strong thoughts or opinions on the public’s perceptions of artist as workers? Do you think that the social view is helpful or detrimental to making it as an artist?

It seems like the majority of the general public are totally dismissive and ignorant about what it takes to do good art. They believe it is an inborn gift. And that you either have it or you don’t. But that is a huge insult to the years of toil and practice we put into it to get to a professional level. The average person thinks we can quickly whip out good stuff with barely any effort and don’t understand why we sometimes charge what we charge. And that since it seems like a fun thing that we do, that we should even do it for free (or nearly so). And with caricatures, I think it’s even more difficult to convey value to the public, because of all the bad street art I mentioned earlier. And also when someone commissions a caricaturist, it’s very often the case that they don’t REALLY want a caricature. Or they don’t trust the artist to make the right decisions. So they try to control every aspect of the drawing and tell the artist how they should draw it. To me, that’s like an average Joe lecturing their mechanic on what they need to do to fix their car. It’s ridiculous to hire a specialized professional and then not let them execute the job the best way they can. So, generally the public’s attitude towards the creative industry makes it difficult to be really successful for an average working artist. But you just have to keep doing it for yourself. Try to do the kind of work that inspires you, put it out there and you will eventually reach the right audience.

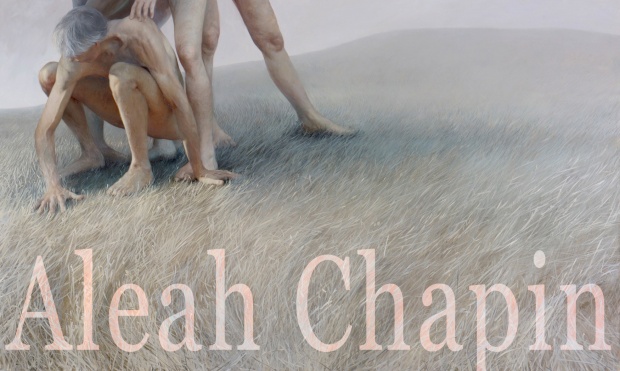

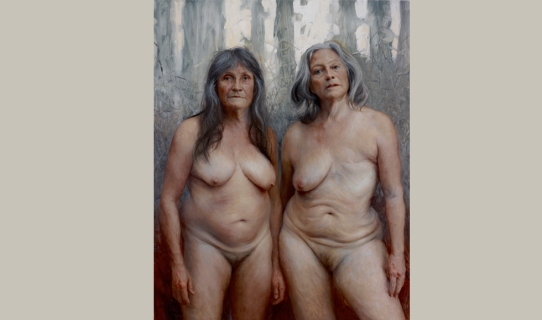

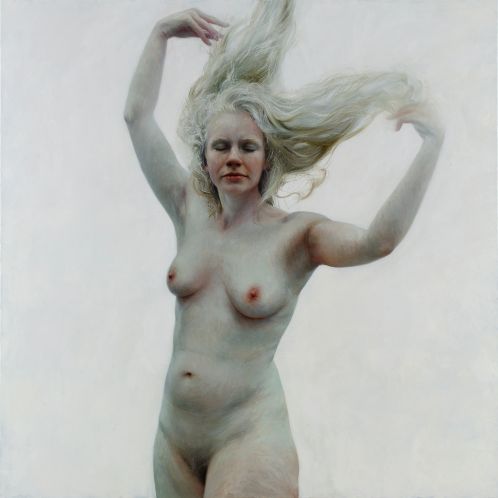

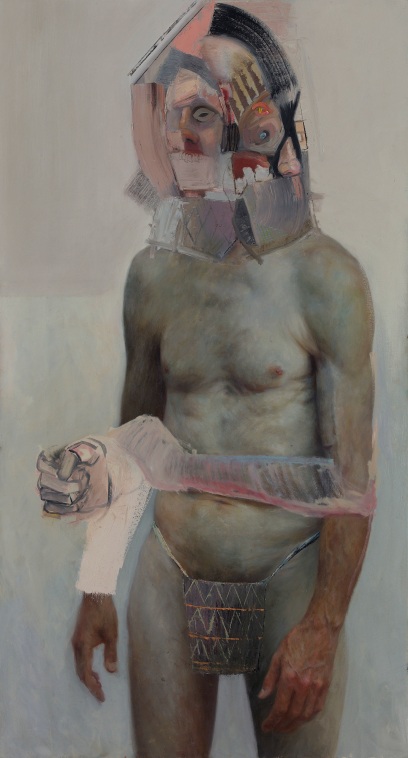

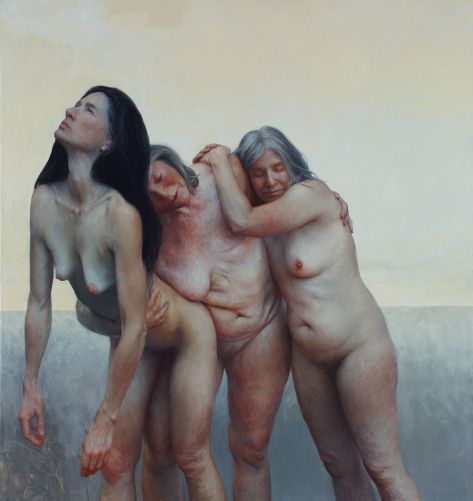

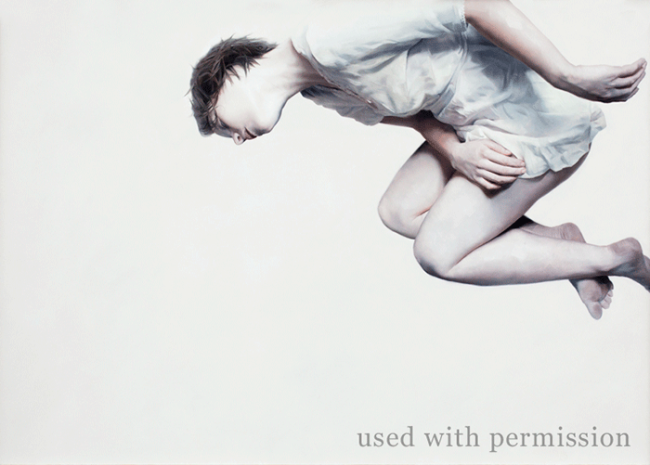

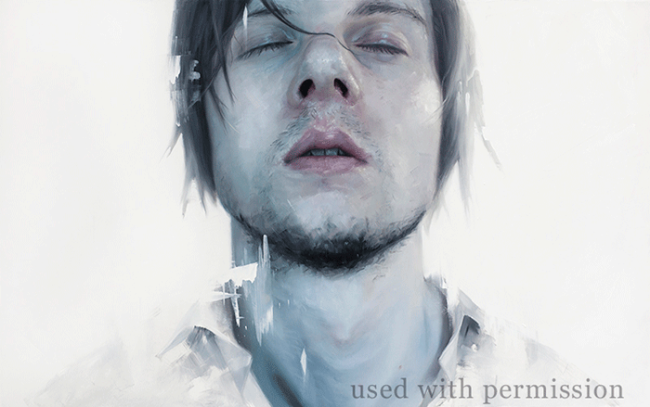

Here is some of Courts amazing work;